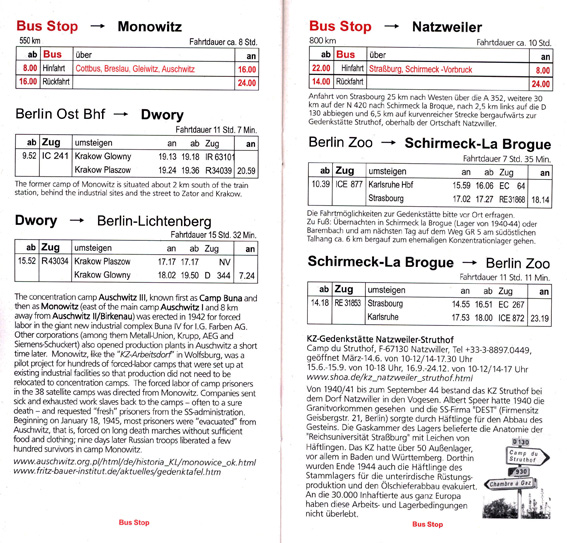

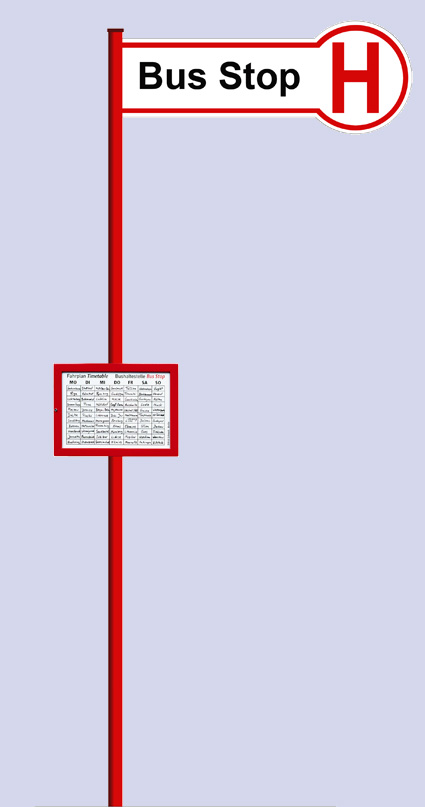

“Anstelle eines Denkmals wollen sie auf dem Areal eine Bushaltestelle einrichten, von der aus rote Busse abfahren zu den realen Konzentrations- und Vernichtungslagern in der näheren und weiteren Umgebung, aber etwa auch nach Auschwitz oder Sobibor. Auf den Bussen stehen das Fahrziel und die Aufschrift “Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas”. So befördern sie die Erinnerung an den Holocaust und den Hinweis auf die Tatorte weg von dem pathetischen Ort im Zentrum der Hauptstadt mitten in den banalen Alltag unserer mobilen Gesellschaft ... Die Präsenz des langgestreckten Terminals aus Glas und der roten, nachts zu einer Lichtskulptur verschmelzenden beleuchteten Busse auf dem als Brache belassenen Gelände bildet gerade in seiner demonstrativen Bescheidenheit eine starke gestalterische Provokation inmitten des teuersten Baugebiets der Hauptstadt. Und auch die Namen der Opfer werden bei Stih und Schnock genannt: in einem Pavillon, in dem man sich anhand von Karten, Publikationen, und interaktiven Computersystemen umfassend über die Organisation des NS-Systems, die Lager und den Holocaust informieren kann ... in jedem Fall stelle sich, so sagen Stih und Schnock ‘der vielbeschworene mündige Bürger einer Sache’. Dieser Akt der Selbstverantwortung der Individuen trete hinter der repräsentativen Gestaltung kollektiven Gedenkens zurück.”

Gabriele Riedle “Die Woche”, 14. Juli 1995

“Rather than a monument, they would like to install a bus stop on the lot. From there, red busses would drive to actual concentration and death camps in both near and distant vicinities, but also to places like Auschwitz or Sobibor. The destination and the inscription “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” is written on the busses. In this way, they redirect remembrance of the Holocaust and the crime scenes away from that lofty site in the middle of the capital right into the banal everyday of our mobile society … The elongated glass terminal and the red busses would meld together to form a light sculpture at night, while the empty lot would remain barren. In its straightforward humility, this would create a strong, formative provocation in the middle of the capital’s most expensive real estate. The victim’s names are also mentioned by Stih and Schnock: in a pavilion where everybody can thoroughly inform themselves about the organization of the Nazi-system, the camps and the Holocaust, using maps, publications and an interactive computer system … in every case, according to Stih and Schnock, the ' conscious, active citizen' comes to terms with the facts. This act of personal responsibility would be lost to a representational design of collective memory.”

Gabriele Riedle, Die Woche, July 14, 1995

taz-Interview 1995-03-28,

Harald Fricke spricht mit Renata Stih & Frieder SchnockBushaltestelle / Bus Stop (please see English translation below)

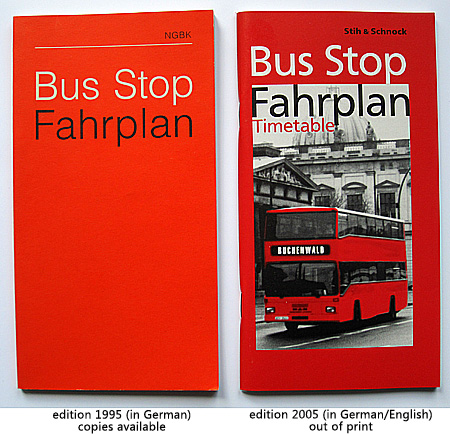

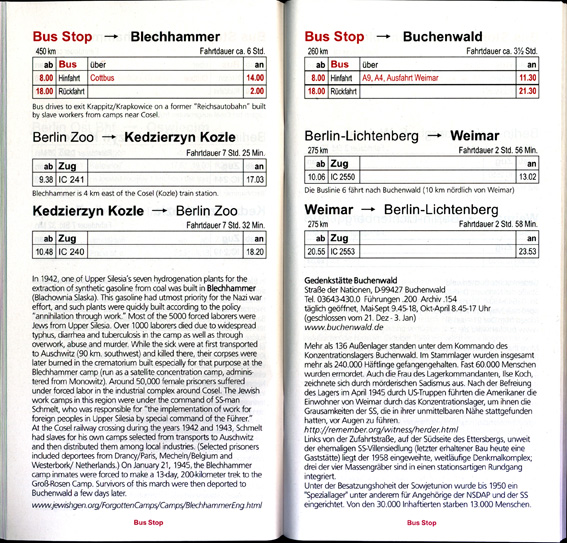

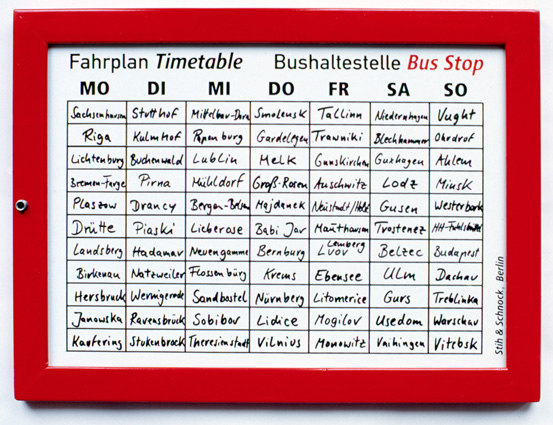

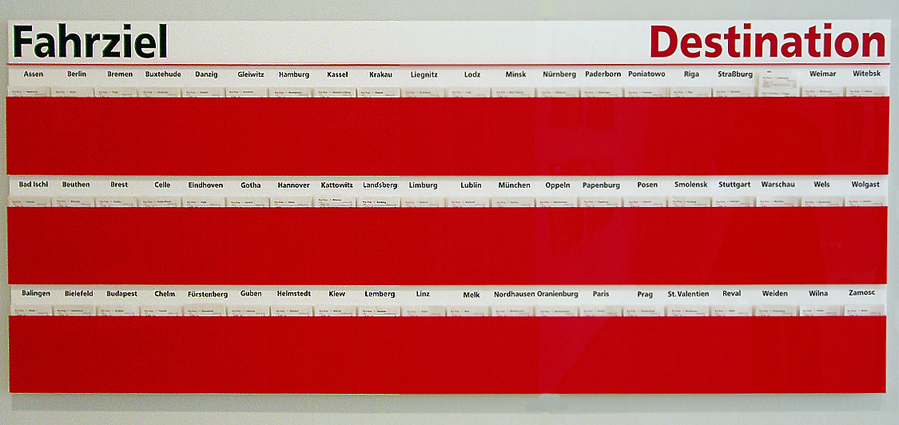

Im Rahmen der IFA-Ausstellung „Stets gern für Sie beschäftigt...“ haben wir zum sechzigsten Jahrestag der Befreiung von Auschwitz diesen Fahrplan erneut aufgelegt. „Bus Stop“ war unsere Antwort auf den Wettbewerb für ein „Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas“. Wir konzipierten es vor gut zehn Jahren. Die Idee der „Sozialen Plastik“ liegt dem Projekt zugrunde, denn mit dem Fahrplan kann sich jeder individuell auf die Spuren der nationalsozialistischen Vergangenheit in Deutschland und Europa begeben. Wie beim dezentralen Denkmal „Orte des Erinnerns“ im Bayerischen Viertel in Berlin-Schöneberg wollten wir ein Kunstwerk schaffen, das durch die Vernetzung von Orten und Informationen ein aktives Gedenken ermöglicht. Denkbar wäre auch gewesen, diese überarbeitete Ausgabe von „Bus Stop“ nur in das Internet zu stellen; aber so kann die kleine Publikation im Auto mitgenommen werden und als alternativer „Zugbegleiter“ den Bahn-Reisenden über Unbekanntes an der Strecke informieren.

Unser Konzept will verdeutlichen, dass man keine monumentalen Konstrukte braucht, um der Opfer zu gedenken. Das ganze Land und viele Teile Europas sind voller Orte und Geschichten, die es gilt, vor dem Vergessen zu bewahren. Beim Besuch der ehemaligen Konzentrationslager macht sich Beklemmung breit, denn die Erde dröhnt und die Ahnung von grauenhaften Geschehnissen, der Blick auf erschütternde Dokumente bleibt unvergessen.

Es ist ein sehr befremdlicher Gedanke, dass Unfassbares durch hohe Betonwände und enge Schluchten nacherlebt, dass mit einer Mischung aus Angst- und Meditationsraum in der Reichshauptstadt die Nähe zum Holocaust simuliert werden kann. Hier wird ganz offensichtlich ein bestimmter Denkmaltypus ersehnt, der die Größe der Trauer über das Geschehene mit der Größe der wiedervereinigten Nation in Einklang bringen soll. Mangelnde Demut hat sich hier in Beton konkretisiert. Der Irrgarten aus Betonblöcken kann den diffizilen Vorgang des Erinnerns und Gedenkens nur verstellen und blockieren. „Mauerspechte“ werden sich vermutlich keine Brocken aus den Betonstelen zur Erinnerung herausbrechen, aber eine Umwidmung zu einem virtuellen „jüdischen“ Friedhof durch das Ablegen einer großen Steinansammlung auf den niedrigen „Grabsteinen“ ist absehbar.

Eine Entsorgungsmentalität ist auszumachen: Ist nun die Zeit gekommen, in der man Schlösser rekonstruiert und den unangenehmen Teil der Geschichte zwischen 1933 und 1945 mit einem so großen Schlussstein versieht, dass er sich als ein abgeschlossenes Kapitel in die Geschichte einreiht? Will man die ehemaligen Lager verfallen lassen und sollen die Firmen und Erben, die von Sklavenarbeit profitiert haben, keine Verpflichtung gegenüber den wenigen Überlebenden haben? Wenn Jugendliche im Rahmen der „Aktion Sühnezeichen“ Hand anlegen, um für den Erhalt der ehemaligen Lager zu sorgen, dann ist dies keine hohle Ersatzhandlung.

Bus Stop ist unabhängig von einem künstlich geschaffenen Gedenkort, nur die organisatorische und inhaltliche Vernetzung mit bereits vorhandenen Gedenkstätten und vergleichbaren Institutionen im In- und Ausland ist unabdingbarer und wesentlicher Bestandteil des Konzepts. Die wenigen bekannten Gräber der Opfer von Todesmärschen, die Häuser mit den Selbsttötungen angesichts unmittelbar bevorstehender Deportationen befinden sich in unmittelbarer Nähe Derjenigen, die Sehen und Wissen wollen.

Es sind die vielen Details, die Zwischentöne und unerwarteten Bilder und Begegnungen, die den Weg zu den Erinnerungsorten eindrücklich machen. Es ist die Zeit die man sich nimmt und den Verstorbenen gibt. Denn der Besuch eines ehemaligen Konzentrationslagers bedarf der Annäherung, um den Erkenntnisschock zu verarbeiten; es ist kein normaler Ausflug. Auf der Fahrt bietet sich die Gelegenheit, Gesehenes und Erlebtes auch im Gespräch mit Anderen zu verarbeiten.

Am Ort des Geschehens sind sie dann da in der schwer erträglichen Leere, ob es sowjetische Kriegsgefangene, Roma, Homosexuelle, Behinderte, Widerstandskämpferinnen, Zwangsarbeiter, politische Häftlinge oder Juden sind. Wer wollte die Nürnberger Rassegesetze der Nazis anwenden, um zu bestimmen, wer Jude ist und daher in einem zu engen Denkmalskontext genannt werden darf? Das Aufsuchen der ehemaligen Lager umgeht dieses unlösbare Problem, denn man gedenkt dort aller Verstorbenen und der durch nazistischen Terror Ermordeten.

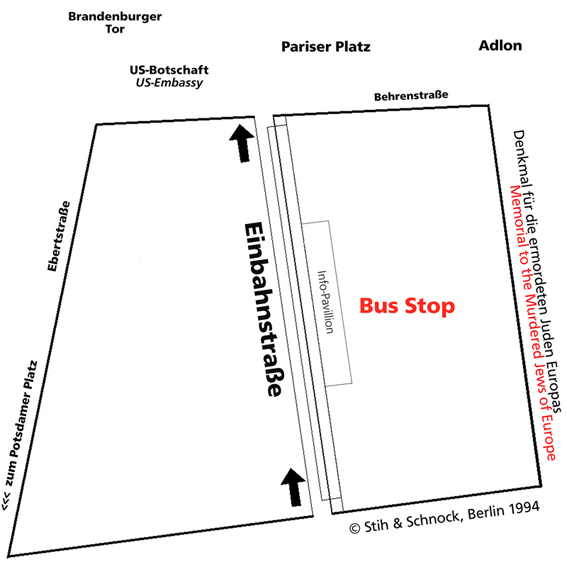

Während in unserem Entwurf eine Einbahnstraße weg von dem künstlichen Denkmalsgelände hin zu den realen Erinnerungsorten führen sollte ist bei dem jetzt realisierten Projekt von Peter Eisenman mit einer Abfolge von unterirdischen Räumen nachgebessert worden. Der dem abstrakten „Denkmal für die ermordeten Juden Europas“ untergeschobene „Ort der Information über die zu ehrenden Opfer und die authentischen Stätten des Gedenkens“ soll eine „Portalfunktion“ übernehmen. Aber warum sollte man/frau in den Keller gehen, um sich Multimediapräsentationen anzusehen? Dient das Zurückkehren aus der Kammer - ans Licht, an die Berliner Luft - der befreienden Erkenntnis? Die Deportationen haben sich in aller Öffentlichkeit zugetragen, darum sollte auch das Erinnern eine wirklich öffentliche Angelegenheit sein. Wer den Ermordeten nahe sein will, der muss sich nicht unter der Erde Filme ansehen oder gar einen Backenzahn aus Belzec mitnehmen; beim Gang um den Schwedtsee, im Wald von Rzuchów und auf dem Sonnenstein in Pirna sind die Lebenden und die Toten allgegenwärtig.

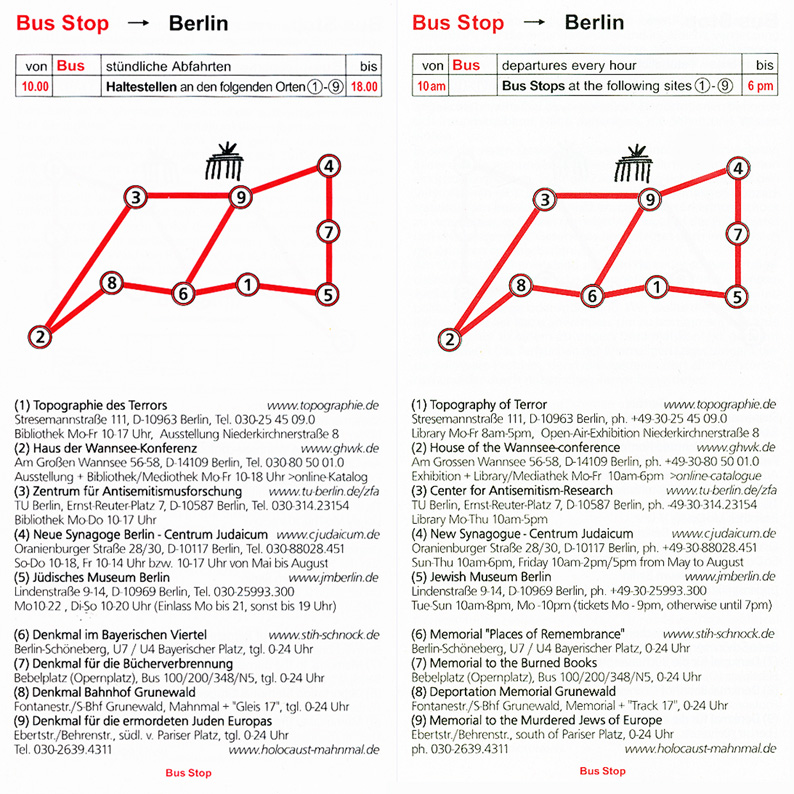

Da es den für die Bushaltestelle vorgeschlagenen Informationspavillon neben der Einbahnstraße nun in medialer, unterirdischer Form gibt ist die Einrichtung einer ständigen Busverbindung nur der nächste folgerichtige Schritt: ein stündlich verkehrender Bus bringt die Besucher des „Denkmals für die ermordeten Juden Europas“ zur Topographie des Terrors, zum Haus der Wannseekonferenz, ins Bayerische Viertel, zur „Bibliothek“ auf dem Bebelplatz und natürlich auch zum Jüdischen Museum. Täglich werden zwei Fahrten nach Ravensbrück und Sachsenhausen angeboten und bei vorheriger Anmeldung sind Besuche von den vielen Orten in- und außerhalb Deutschlands auf dem Programm.

Vorab kann sich der/die geneigte LeserIn in dem vorliegenden Fahrplan schon einmal über mögliche Ziele informieren.Renata Stih und Frieder Schnock, Berlin 2005

BUS STOP brochure excerpt > click here !

In conjunction with the IFA exhibit “Stets gern für Sie beschäftigt...“ (“Always at Your Service …”) and in honor of the sixtieth anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, we have published a newly edited version of this schedule. “Bus Stop” was our answer to the competition for a “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” We developed it about ten years ago. The art project’s basic concept is the idea of a “social sculpture,” as every individual can use this publication to follow the traces of National Socialism in Germany and Europe. We wanted to create an artwork that would make possible an active process of remembrance through a network of information and places, quite similar to the decentralized memorial in the Bavarian Quarter, “Places of Remembrance” (“Orte des Erinnerns”, Berlin-Schöneberg 1993). Instead of posting “Bus Stop” in the Internet for downloading, we intended this small publication to accompany travelers in their cars and serve as an alternative “Zugbegleiter” (“train guide”), which will inform the railway traveler about unknown destinations along the route.

We want to make clear that there is no need for monumental construction in order to commemorate the victims. The entire country and many parts of Europe are full of places and histories that must not be forgotten. A visit to a former concentration camp creates uneasiness; the earth trembles, and the knowledge of atrocious events as well as glimpses of devastating documents are seared into memory.

It is a very strange idea that says that the incomprehensible can be experienced through tall concrete walls and narrow passages, or that a sense for the Holocaust can be simulated by a space attempting to generate a mixture of Angst and meditation in the middle of the new capital. A specific kind of monument is obviously longed for, one that strives to reconcile the enormous regret about the past with the greatness of the reunited nation. The lack of humility has cast itself here in concrete. The labyrinth of cement blocks can only obstruct and block the difficult process of remembrance and reflection. “Mauerspechte” (“Wall wood-peckers”) probably will not chip off pieces from the concrete blocks, but it is predictable that people will transform the memorial into a virtual “Jewish cemetery” by depositing small rocks upon lower “gravestones.”

Apparently, “history-light” has caught on: Is it the time to reconstruct palaces and to use such a great capstone to seal off the uncomfortable part between 1933 and 1945 as a closed chapter in history? Do we want the former camps to fall into decay, and is there no responsibility on the part of those companies and heirs who profited from slave labor toward the few survivors? By contrast, it is no hallow gesture for young people to work with the “Aktion Sühnezeichen” in keeping up the former concentration camps.

“Bus Stop” is independent from an artificially created memorial site; fundamental and instrumental is the close link to existing memorial sites and comparable institutions both here and abroad. Wherever they go, those who want to see and know will recognize the few burial sites of death-march victims and houses where people facing deportation committed suicide.

Details, nuances, unexpected images and encounters turn the approach to memory sites into a formative experience. You take your time and you give it to the dead. Going to a former concentration camp is no simple day trip: it requires preparation in order to be able to stand the shock of comprehension. The way back offers the opportunity to talk about things seen and experienced.

At the actual sites they are all there in the unbearable emptiness, whether they are the disabled, prisoners of war, Roma, homosexuals, resistance fighters, forced-laborers, political prisoners or Jews. In the all-too limiting context of the monument, no one wants to apply the Nuremberg Race Laws in order to declare who is a Jew and who is not. Going to former concentration camp avoids this problem, for one remembers there all those who were tortured and murdered through Nazi terror.

In our project, an “Einbahnstraße” (one-way road) leads away from the artificial monument to the real memorial sites — a connection that was missing in the Eisenman project. In order to compensate for this, a subterranean space had to be added to the abstract “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe.” The underground information center will “provide the necessary background material on the victims commemorated here and on historic memorial sites. A central function of the information center is to back up the abstract form of remembrance inspired by the Memorial with concrete facts and information about the victims.” (Quoted from the official memorial web site.) But why should one stand in line to go into the basement just to watch multi-media presentations? Does the return from the chamber to the light and Berlin’s open air serve as a liberating revelation? The deportations took place in public; that is why remembrance must truly be a public issue. If you want to be close to the murdered, there is no need to see movies below ground or take a molar from Belzec; if you walk around the Schwedtsee, in the Rzuchow forest or on the Sonnenstein in Pirna, the living and the dead are all around you.

Considering that our project "Bus Stop" had proposed an information pavilion next to the “Einbahnstraße” and that this idea has now materialized in an underground form, it is only logical to install a regular bus connection. A bus commuting hourly will bring visitors from the “Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe” to the Topography of Terror, to the House of the Wannsee Conference, to the Bavarian Quarter, to the “library” on Bebelplatz, and, naturally, to the Jewish Museum. There will be two daily busses going to Ravensbrück and Sachsenhausen, and by announcement, to more places in and outside of Germany.

Until then, readers so-inclined may inform themselves about possible destinations with this schedule at hand.Renata Stih und Frieder Schnock, Berlin 2005

excerpts from the Bus Stop - publication

(German/English, 2. ed. 2005) below:

actual realisation see below,

view towards Potsdamer Platz:

view towards Adlon Hotel & China Club

(with a sign addition on the left):

(c) Stih & Schnock, Berlin / VG BildKunst Bonn / ARS, NYC